Tags

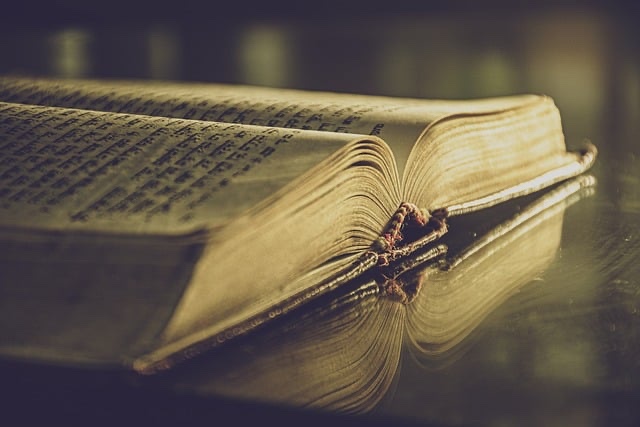

In the turning of the Jewish year, each summer we come to the beginning of the Book of Words, D’varim, known as Deuteronomy.

Every year I have the same reaction, almost recoiling from the angry words coming from Moses’ mouth. The entire book is told in his voice, and almost immediately he tells stories we already know from the Torah. But this time the stories are retold, almost twisted, to his perspective.

I pause, remind myself that this is what we humans do. We are each the hero of our own narrative and we cannot help but tell our stories in our own voice.

Often, I have sat with family members after the death of a loved one, and they will disagree vehemently about the facts of a well-known family story. Each remembers it differently. Sometimes one person is the hero, sometimes another. Each is bewildered that anyone could remember it differently.

The final book of the Five Books of Moses is this leader’s chance to tell the story his way, without interruption. His siblings Aaron and Miriam are both dead, as are all of the people who he led out of Egypt. The book is his message to their children and grandchildren as they prepare to enter the Promised Land, promised but not given to their forebears.

There is no one to contradict him except Caleb and Joshua, the only ones from Egypt to be allowed to live. Of course there’s God too. But the God of this book is distant; spoken of, but not speaking directly. This is Moses’ story to tell.

And I remind myself that this is not the Moses we met in Exodus. When he stood at the burning bush he was 80 years old. Four decades later, he is a different man. No longer hesitant, this Moses does not stutter. He is eloquent, alternating between chastising the people and encouraging them.

Like Moses, I too am a person of words. I am a writer, a storyteller. I know that sometimes a story must be tweaked, given a little shove to go in the desired direction. But it must remain honest or it will fall flat, leaving the listener dissatisfied and disgruntled.

Rabbi Elliot Cosgrove wrote, “There are, to be sure, numerous ways to measure a life of leadership, but at the core truly great leadership requires a correspondence between an individual’s inner and outer lives.”

Moses spoke his truth, sometimes angrily, sometimes despairingly, always honestly. Human and fallible, he did his best with an unruly group of followers who themselves were prone to revisionist history. However we see him as we look back, may his memory be for a blessing.